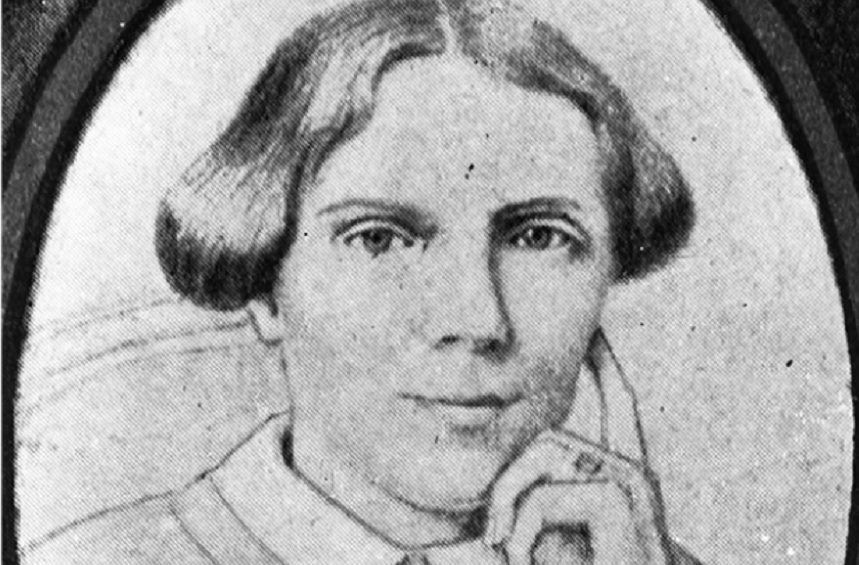

The first female doctor to change the face of women’s healthcare

Elizabeth was born in 1821 in Bristol, England, and was one of nine children. Her father, a sugar refinery owner, was active in the anti-slavery movement and wanted his daughters to have the same educational opportunities as their brothers. In his autobiography, he described his childhood as “very happy, rich and fulfilling years”.

When he was 11 years old, after a sugar refinery fire, the family moved to the United States in search of job opportunities and progressive ideas. They spent the next six years in New York City, the suburbs of Long Island, and New Jersey. Elizabeth attended school and launched herself into the anti-slavery movement, attending anti-slavery rallies and stitching them into fundraising fairs to abolish slavery.

In 1838, at age 17, with his father’s new sugar refinery in trouble, business prospects drew the family to Cincinnati. He wrote that they were “filled with great hope and anticipation.” But within months of his arrival, his father passed away, leaving the family bankrupt.

To support the family, Elizabeth and her sisters opened Young Women’s Day and boarding school. He closed it after a few years and Elizabeth continued to teach in various states. During this period he met a dying family friend who changed his life.

He wrote in his diary: “The idea of obtaining a doctor’s degree took little by little from a great moral struggle, and the moral struggle attracted me greatly.”

His teaching jobs have taken on a new meaning: earn money to finance his education. She held a position as a music teacher in South Carolina, staying with the family of a distinguished doctor who gave her access to his extensive medical library, and spent all her free time studying.

Soon, she applied to more than 20 medical schools and “it was not surprising that they turned it down all,” says Dr. Tong. “Fortunately, he had a tutor,” a respected physician, wrote a letter on his behalf to the Geneva Medical School in North York.

On October 20, 1847, Isabelle received a letter of acceptance that became her most prized possession. The letter indicated that her acceptance was put to a vote by all medical students who voted in the affirmative. “Legend has it,” says Dr. Tong. “They thought it was a joke.”

“Award-winning zombie scholar. Music practitioner. Food expert. Troublemaker.”

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/AHVYMMDSTZDTDBFNZ3LMFUOKNE.jpg)